Guest Post: 'Restore Roe' Isn't Enough

"Roe almost killed me. We must end all government interference in pregnancy."

Dr. Layla Houshmand resides in the Washington DC Metro area with her husband. She is a medical device commercial strategist with a PhD in biomedical engineering.

By Dr. Layla Houshmand

When I was eight-weeks pregnant, I was denied an emergency abortion and lost most of the vision in my right eye as a result. But this isn’t a post-Roe horror story. I was living in deep-blue Maryland, financially secure, and armed with a medical background, but abortion restrictions still endangered my life. That’s why I can’t support calls to ‘restore Roe’.

Roe almost killed me. We must end all government interference in pregnancy.

My husband and I planned carefully to start a family. When I became pregnant again after an early miscarriage, I worried for both the baby’s health and my own. Pregnancy can be a brutal experience for women, with no guarantee of a baby in the end. That was a risk I was willing to take in Spring 2021.

In my case, risks became costs. I didn’t know that pregnancy would make me a second-class citizen inside of my own body.

At eight weeks pregnant, I woke up with a severe headache and blurred, distorted vision in my right eye. Within hours, I was in an ophthalmologist’s office, vomiting violently, unable to stand. She believed that pregnancy caused a stroke in my optic nerve—an imperfect diagnosis that did not fit all my symptoms, but one that meant risking permanent vision loss. But the necessary diagnostics and potential treatments were deemed unsafe during pregnancy.

I felt the air in the room thin when she said, “There’s nothing I can do for you because you’re pregnant”.

Indignant, I told her that I’d have an abortion. I was not willing to sacrifice my vision for my eight-week-old embryo. What if her diagnosis was wrong and I was in even more danger? How could I recover any vision if I stayed pregnant and miserably sick?

Incredibly, my pro-choice OB-GYN could not help me. The medical assistant who answered my urgent phone call refused to let me speak with a doctor. I would not have qualified for an abortion in the religious hospital where my doctor practiced. Even under Roe, religiously affiliated hospitals could refuse to provide abortion care. One in five US hospital beds is in a religious hospital, and many Americans have no choice but to seek care in one.

But I was lucky. I convinced a nearby abortion clinic to schedule me for the following morning, and I could afford the $950 for an abortion with sedation. Fortunately, in Maryland there are no government-imposed waiting periods for abortions. Left alone with no medical advice or support, my “medically necessary” abortion became an “elective” one.

It turns out that the original ophthalmologist had missed my rare diagnosis: a rapidly spreading viral infection for which I was admitted to a specialty eye hospital. The immunosuppression of pregnancy activated the very common virus that causes cold sores; left untreated, I risked complete blindness and death. Despite my world-class medical care, including five surgeries, the delay in accessing an abortion allowed that virus to cause significant permanent vision loss.

This is an example of the best-case scenario under Roe: a permanent disability due to a delay in abortion care. Despite being medically literate, financially secure, able to consult experts—and even having personal connections at major nearby hospitals—I couldn’t obtain faster treatment. What would have happened to anyone else?

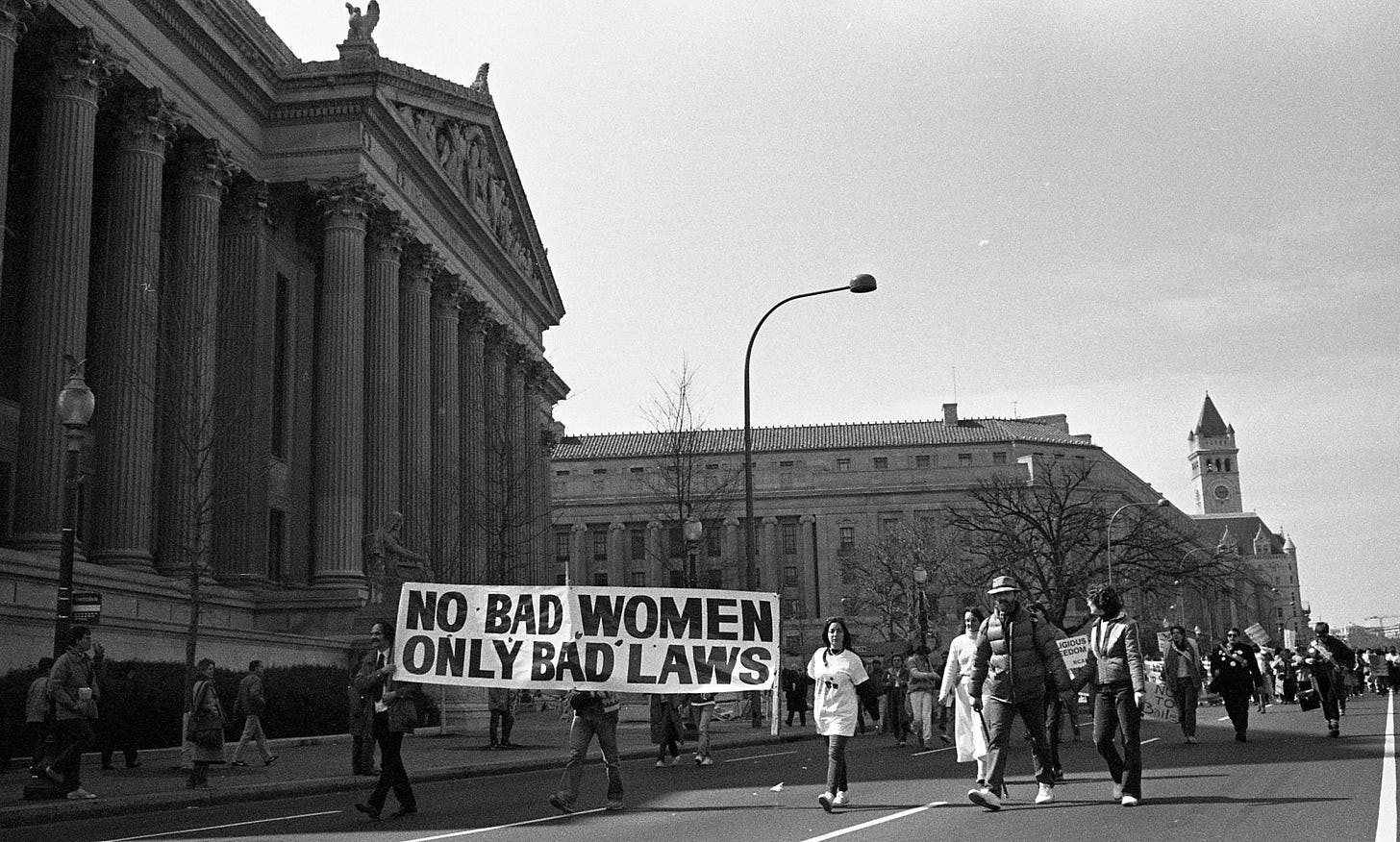

None of us should be surprised. In the half-century when Roe was law, anti-abortion advocates strategized and lobbied towards the bold goal to outlaw all abortion. They pushed abortion into the periphery of medicine one step at a time: the Hyde Amendment, unreliable ‘viability’ limits, state-mandated waiting periods, religious refusals of care, and so many more.

These so-called “reasonable compromises” stigmatized abortion, a stigma that remains deeply embedded into medical care for all pregnant patients.

Of course, the situation is so much worse now. States want to criminalize doctors for providing lifesaving abortions, miscarriage patients are being forced to go into sepsis and nearly die before getting care, and raped children are being forced to give birth or travel out of state for an abortion—if their state doesn’t criminalize that, too.

Getting out of this mess requires working towards a dramatic transformation of standard of care in pregnancy, one that prioritizes existing life over potential life by taking government out of the equation. If that feels radical, it’s proof of how fast and far the Overton Window has shifted.

There is nothing radical about bodily autonomy. There is nothing more basic than wanting to be safe in our own bodies.

Pregnancy is not health-neutral–it is a risk that requires continuous consent. “Restore Roe” is a nice slogan, but we deserve a better system. Roe was a poor compromise that left patients even like me relying on luck. And systems based on luck aren’t systems at all.

I believe Catholic hospitals are largely responsible for our lousy maternal mortality rates. How can they not be when they refuse to help women who come to them with ectopic or molar pregnancies or miscarriages? Time is of the essence in these cases, but they don’t care and I have to believe they have killed or maimed many women through the years. Catholic hospitals cannot be allowed to continue to deny care when we restore women’s healthcare rights. It’s barbarism in this day and age. (Personally, I would like to see no religious hospitals allowed in this country. People are at their most vulnerable in hospitals and they shouldn’t be worried about someone’s religion dictating their care, or lack of care.)

I have been thinking about this for awhile now. I'm lucky to live in Baltimore where we have lots of good hospitals, but a huge portion of them, including the one where the majority of my own healthcare is done, are Catholic hospitals. In this country we have relied far too much on charities for healthcare because of our for-profit health setup. It's costing too many people in too many ways.